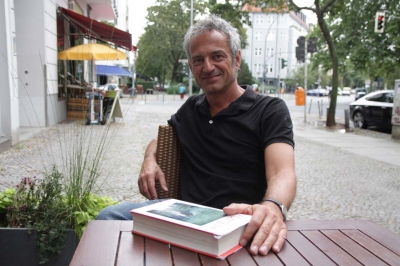

Professor Dr. Iwan D'Aprile Visits From Uni Potsdam

Prof. Dr. Iwan D’Aprile, literary historian and chair of the professorship “Kulturen der Aufklärung” at the Universität Potsdam, visited us at Duke for a week in late September. He presented his latest book, Fontane. Ein Jahrhundert in Bewegung, talking about his goal of describing Fontane in the context of his cultural-historical background as well as the specific challenges and pleasures of writing in the genre of biography for a general audience. Prof. Dr. D’Aprile was also generous enough to guest lecture in Dr. Engelstein’s graduate seminar on Kleist as well as Dr. Gellen’s graduate survey on the history of German literature (nineteenth century to present). After that considerable intellectual engagement, he then traveled to Portland to present the paper “Mimesis of Media: Journalistic Practices and Realist Poetics in Theodor Fontane” at the German Studies Association annual conference. The faculty and graduate students were delighted to have the chance to engage with one of our European colleagues, to hear about his book, and to speak some German!

What did you especially enjoy doing during your visit at Duke?

I had an exciting and inspiring time at Duke. I received an incredibly warm welcome and lots of support by the German Department’s staff Margy and Dorothy. Heidi Madden gave me an insight into the rare books collection of Duke’s library, including fascinating copies from the Baroque era. 24-hour opening hours at the library was a new experience to me, as I have never seen this at German universities. I also had many interesting and fruitful conversations with my colleagues Stefani, Jakob, Kata, and Thomas, in which we shared lots of ideas for an intensified co-operation between our institutions. Last but not least, I enjoyed very much the seminars with the CDG graduate students. I was impressed by the students’ intense preparations, thorough and thoughtful readings, surprising observations, and insightful questions. All in all, my stay at Duke was much too short and I was sad to leave.

How did you get into studying German?

Already during my graduate studies in Germany, my interest in German literature was quite broad, also comprising history and philosophy – much more in the sense of American German Studies. Taking the period of the Enlightenment as an example, which was my first field of specialization, one cannot understand Lessing’s works without knowing Spinoza or Leibniz, nor Schiller’s without Immanuel Kant. I was always interested in the social, political, medial, and discursive historical contexts of literary texts. Or take an author like Theodor Fontane, on whom I wrote my last book. During his entire life, Fontane moved between journalism and literature, internalized the conditions of 19th-century literary production in the context of new mass media such as newspapers and photography, and published historical works as well as fictitious ones. You need cultural history, history of the press, as well as knowledge of the literary developments of that period to comprehend such a phenomenon.

One of your interests is the history of journalism. What are your thoughts on contemporary journalism – the attempt to revive long-form journalism, the use of Twitter/Facebook, and so on? Do you have any favorite magazines, newspapers, or journalists?

Not only Fontane, but in fact many prominent authors must be seen as “literary journalists,”from Ludwig Börne and Heinrich Heine to Georg Hermann, Siegfried Kracauer, Georg Roth, Vicky Baum and Gabriele Tergit. Karl Marx published almost only newspaper articles throughout his life time – whereas his canonical works such as Das Kapital are posthumous publications. Of course, the medial change from paper to digital publishing will bear new literary forms. But as I have tried to show with Fontane, already some of his novels can be understood as a literary adaptation or “duplication” of the medial public discourse of his times encompassing and transforming political world news, local stories, and advertisements, or “Reklame” as it was called in the 19th century. I still read paper journals and I love long-form journalism in the Anglo-American tradition of the London Review of Books, The Guardian, the New Left Review, or the New Yorker.

Tell us about an item on your bucket list!

This year is still fully occupied by Fontane. I am working on my contribution to the new Fontane handbook, which will appear in 2020, as well as on some research articles coming out from the manifold interesting conferences of the Bicentennary – including the GSA. Next year I will think about a new project. In this regard, coming back to the US for a more extensive research stay is definitely on my bucket list.

Anything else to say about the visit to Duke/the GSA, writing in general, or German literature?

I was impressed by the new generation of Germanists emerging at US universities. The long and strong 20th century tradition of German Studies in the US is owed very much to exiled, mainly German-Jewish intellectuals and their immediate academic disciples – among them the big names of German intellectual history. Currently, German Studies has to face the challenge of building upon their heritage, in terms of intellectual horizons and critical thinking, and at the same time of developing innovative new ways to keep it an attractive and relevant field of study. Both at Duke as well as at the GSA, I was very glad to learn that there is still a vivid and most fruitful interest in German literature.